Introduction

In the early 2010s, the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services agency (USCIS) reached a turning point. Chronic underfunding and a persistent lack of human resources combined with a growing number of clients resulted in overworked staff and frustrated clients. Recognizing how unsustainable this was, USCIS decided to create a customer service chatbot named Emma, after the poet Emma Lazarus whose poem is inscribed on the Statue of Liberty (USCIS, 2018). This chatbot would live on the USCIS website, appearing in the form of an icon at the top right of users’ screens and designed to answer general questions regarding U.S. immigration and citizenship processes. In December 2012, Emma was officially launched on the USCIS website. USCIS has since declared Emma a resounding success, having greatly reduced the number of clients calling the customer support line and even going so far as to grant Emma the Service to the Citizen award (Verhulst, 2017; Temin, 2018).

Not everyone believes Emma to be the success USCIS claims the chatbot to be. Concerns surrounding data privacy, storage of personally identifiable information (PII), security of the chatbot interface, how data gathered through Emma can be used, and even perpetuation of gender stereotypes have been raised over Emma’s 10 years (Sanchez, 2016; DHS, 2017; Murtarelli, 2020; McDonnell, 2019). The following sections explore these concerns while also considering the successes Emma has faced, in the context of immigration and chatbots more generally, to provide an understanding of the implications of artificial intelligence (AI) adoption in U.S. immigration processes.

Background on Customer Service Chatbots

To understand the nature of Emma, it is important to first develop an understanding of customer service chatbots more generally. Customer service chatbots, also known as virtual agents, are the most popular type of chatbot and are the ones that appear to have the greatest impact on customer experience and the organization’s goals (Kannan, 2019). Virtual agents use AI to “understand” and respond to customers’ questions, thereby simulating human conversation (Hingrajia, 2001; Kannan, 2019). There are two main types of customer service chatbots: rule-based and AI-based (Hingrajia, 2001). Rule-based chatbots use machine learning and manual training to answer clients’ questions based on a pre-programmed list of questions and answers (Hingrajia, 2001). AI-based chatbots are more complicated. This type of chatbot uses deep learning to understand and appropriately respond to a wider range of questions and “learn” as it interacts with humans (Hingrajia, 2001). You can boil the differences between the two systems down to this: rule-based chatbots rely on human intervention to improve while AI-based chatbots can improve on their own. For this case study, we will focus on AI-based chatbots as that is the category in which USCIS’s Emma falls.

Chatbots are becoming increasingly popular among businesses. Some estimates point to over 80% of organizations increasing their investment in chatbot technology over the next few years (Murtarelli, 2020). This is largely due to the effectiveness of chatbots in reducing client wait time, increasing client satisfaction, and decreasing organizations’ costs over the long term (Murtarelli, 2020; Hingrajia, 2001; Kannan, 2019). However, there are costs to implementing and operating chatbot technology. Firstly, the initial costs of creating an effective AI chatbot can be high. This includes feeding the chatbot thousands of chat or call transcripts so the chatbot can learn (Kannan, 2019). Additionally, it can take months to train and develop a chatbot, which can be a significant drain on resources (Kannan, 2019).

Specifications of Emma

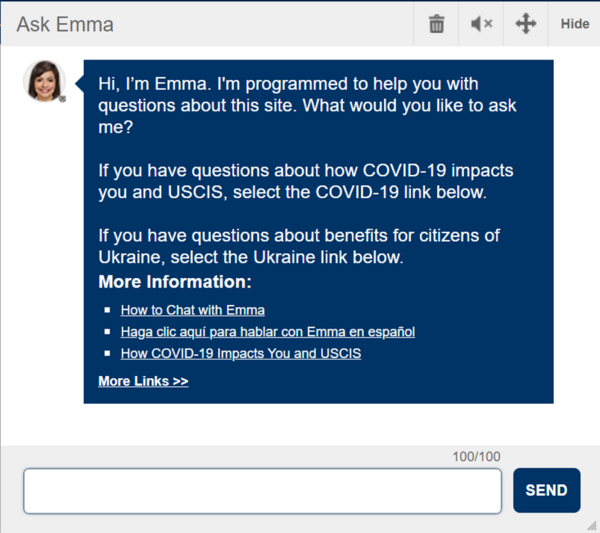

“Need Help? Ask Emma” invites users to come to Emma with their questions. Upon clicking on Emma’s icon, users are greeted with a list of frequently asked questions (FAQs) and are presented with the opportunity to click the FAQ that matches their question or to ask Emma a question if their question does not match any of the provided FAQs. The AI-based chatbot was created by the USCIS to answer questions, in both English and Spanish, that visa applicants have about various immigration processes, to guide applicants through the USCIS website, and to refer individuals to resources that they may find helpful (USCIS, 2018). Emma cannot answer questions about an individual's visa status and refers clients who ask about their status to a live agent (USCIS, 2018). Relatively little is known about the specifics behind how Emma was created beyond that USCIS paired with Verizon and the tech company Verint (previously NEXT IT) to create the program (Verhulst, 2017). Emma was trained using machine learning algorithms and, theoretically, should be able to understand most questions and get “smarter” the more the program interacts with users (Boyd, 2015). In practice, however, Emma does not learn entirely on her own. While Emma does improve her responses based on her previous interactions, USCIS operates a team of human developers that interfere in this process and make decisions on how best to improve the quality of her responses beyond Emma’s own “learning” (Boyd, 2015; DHS, 2017). This human interference speeds up the learning process and improves the customer experience at a faster pace.

Before Emma, the only way to contact USCIS with questions was through the agency’s phone number and most of the over 1 million monthly calls to USCIS were from clients asking about information that was available on the USCIS website (Boyd, 2015). Given the immense drain on human resources and the lack of agency capacity to handle this increasing number of calls, Emma was a much-needed addition to the team. Not only did Emma reduce the budget and human resource strains, but she also increased her capacity by being able to answer clients’ questions 24/7 (USCIS, 2018). The USCIS website states that Emma answers an average of 456,000 questions per month, is used nearly twice as much as the website’s search feature, can correctly answer 90% of commonly asked questions in English and 86% in Spanish, and has reduced the amount of time clients spend searching for information on the USCIS website (USCIS, 2018). While Emma may have had success in reducing the number of human resources needed by USCIS, there are also a plethora of how-to videos, tutorials, and blogs teaching people how to bypass Emma and speak to a human agent. This suggests that visa applicants prefer to speak with a human and that Emma may not be as effective as she could be in reducing the number of calls USCIS agents take.

Ethical Concerns with Chatbots and Emma

Apart from these initial startup costs, there are also ethical concerns with the use of chatbots. These ethical concerns have largely to do with data privacy. Some ethicists argue that chatbots, which are designed to simulate human conversation, encourage the humans they interact with to share more information than is needed, potentially exposing clients’ PII if the chatbot site is not secure (Murtarelli, 2020). Similarly, concerns have been raised surrounding the storage of chatbot conversations, which includes the potential storage of PII (Murtarelli, 2020). Organizations that collect PII typically have stringent processes and precautions in place to prevent potential leaks of information. In the case of clients volunteering PII where the intention is not necessarily to collect PII, as is often the case with chatbots, likely the processes intended to protect data privacy are not in place. However, this may simply be a matter of organizations recognizing this risk and proactively implementing data privacy protection procedures, such as immediately deleting chatbot conversations, as a precautionary measure.

Additional concerns have been raised surrounding the information asymmetry in client-chatbot interactions (Murtarelli, 2020). As previously mentioned, chatbots are designed to answer clients’ questions. This process is facilitated by collecting data on the client with whom the chatbot is interacting to better assist the client (Murtarelli, 2020). This can be considered predatory behavior as the data collected by the chatbot may serve the needs of the organization over those of the clients. For example, in the case of Emma, client information gathered from Emma may provide insight into migration patterns (if there are elevated numbers of individuals asking Emma about certain immigration processes) which could then be used to place entry-prevention methods in place, depending on the agenda of the administration in power. This, of course, would be in direct contrast to the interests of the clients using Emma, who aim to enter the U.S.

Finally, a separate concern unrelated to data privacy is that of chatbots perpetuating gender stereotypes. This can be seen in the ascription of female identity to most customer service chatbots, thereby perpetuating the stereotype of women belonging in customer service or supportive roles (Feine, 2020). Other studies have shown the effect of chatbots’ apparent gender on client satisfaction and gender stereotypical beliefs (McDonnell, 2019). Research on this topic is somewhat sparse, but it is nonetheless an important factor to take into consideration when evaluating the implications chatbots have on society. Subsequent sections will evaluate Emma and the potential challenges that arise in the chatbot’s usage as they pertain to the ethical concerns outlined in this section.

As with other chatbots, Emma generates some data privacy concerns both inside and outside USCIS. What sets Emma apart from other customer service chatbots is the power imbalance present in the relationship between USCIS and its clients, which places Emma in a position of authority and may contribute to an increased risk of data privacy loss. For example, while Emma clearly states that she is a chatbot upon starting a conversation with individuals, and uses a robot-like voice for the audio feature, there are records of clients interacting with Emma and volunteering PII about themselves because they believe it is necessary to get their questions answered (Boyd, 2015). While disclosure of PII is common with all chatbots, Emma’s role as a USCIS “employee” likely generates increased feelings of pressure on the part of clients to disclose PII to get satisfactory answers to their immigration questions. Emma does not disclose that the information shared in conversations with her is not confidential. Additionally, Emma automatically collects information about each interaction, including date and time of visit, content visited, IP addresses, and server data, and stores this data for up to two years (DHS, 2017). This technical data, combined with personal data volunteered by individuals, could provide ample information for hackers to steal identities. This information could also be used to target undocumented immigrants conversing with Emma to seek pathways to citizenship or other documentation. A 2017 joint report from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and USCIS explicitly states that one of the risks to clients interacting with Emma is that USCIS may inadvertently share information without the client’s consent (DHS, 2017).

USCIS is aware of the privacy concerns raised by Emma’s usage and is taking steps to address them. This includes immediately deleting chat history once the chat is complete (allowing Emma to learn from the interaction herself and eliminating the need to store the data, except for the aforementioned technical data which can be stored for up to two years), masking all PII offered by clients in chats, limiting access to chat data to a limited number of USCIS personnel who have received data privacy training, and sharing conversation logs on a “need to know” basis (DHS, 2017). Despite these measures, the risk remains. Questions circulate surrounding what a “limited number of personnel” and “need to know basis” mean. Are individuals seeking to use this information to target and deport undocumented immigrants included in the “limited number of personnel” with access? Does deportation constitute a “need-to-know” basis? Risk remain, however mitigated it might be.

Finally, concerns surrounding the perpetuation of gender and racial stereotypes through the use of Emma as female and Latina-presenting emerge (Villa-Nicholas, 2019). The use of Emma as a female-presenting chatbot may promote the stereotype that women, and in this case specifically Latina women, belong in the service industry (Villa-Nicholas, 2019). In conjunction with this, it could also be argued that the portrayal of Emma as a Latina enforces the notion of the existence of an “ideal immigrant”, that being one that is helpful, tech-savvy, and speaks English, thereby enforcing this concept into the consciousness of immigrants that interact with Emma (Villa-Nichols, 2019). By contrast, it could also be argued that the likelihood of this portrayal meaningfully impacting potential immigrants in the short span of interaction they may have with Emma is likely minimal.

Future of Emma

While Emma has generated several successes both for USCIS (reducing costs and increasing capacity) and individuals seeking immigration information (ease of access and reduced waiting times), there remain several data privacy concerns, specifically surrounding who has access to stored chatbot data. Individuals who use Emma should refrain from volunteering any PII and should ask only general immigration or citizenship questions. Anything specific should be (and often is) directed to a USCIS live agent. Other governments seeking to implement technology similar to Emma's should consider the risks that it may pose to individuals and should implement data privacy practices such as immediately deleting ALL chat-generated data upon completion of the chat. Implementing preventative measures such as this would reduce the risk to clients while retaining benefits for the agency, and should be considered standard practice for any chatbot.

Appendix

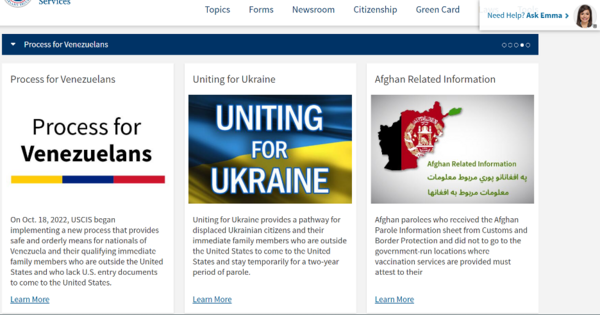

Figure 1.

Image taken from the USCIS website https://www.uscis.gov/

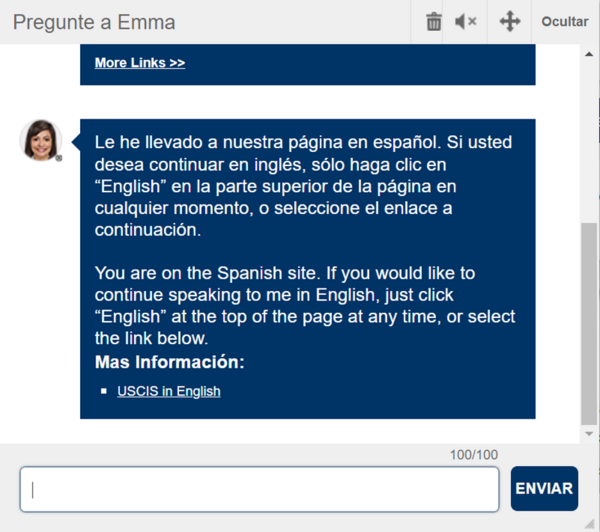

Figure 2.

Image taken from the USCIS website https://www.uscis.gov/. Emma was recently updated with the ability to speak in Spanish. Previously, the audio feature was only available in English. Emma remains unable to understand human speech and relies on text for communication.

Figure 3.

Image taken from the USCIS website https://www.uscis.gov/

Bibliography:

- Boyd, Aaron. “USCIS Virtual Assistant to Offer More ‘human’ Digital Experience.” Federal Times, November 16, 2015. https://www.federaltimes.com/it-networks/2015/11/16/uscis-virtual-assistant-to-offer-more-human-digital-experience/.

- DHS, and USCIS. Rep. Privacy Impact Assessment for the Live Chat. USCIS, 2017.

- Feine, Jasper, Ulrich Gnewuch, Stefan Morana, and Alexander Maedche. “Gender Bias in Chatbot Design.” Chatbot Research and Design, 2020, 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-39540-7_6.

- Fullerton, and Carman. “Lexington Chat Bot Emma | KY Immigration Attorney.” Carman Fullerton, August 10, 2016. https://carmanfullerton.com/emma-learns-spanish/

- Hello, I'm Emma. How May I Help You? YouTube. USCIS, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9MQFewDeaCM.

- Hingrajia, Mirant. “How Do Chatbots Work? A Guide to the Chatbot Architecture.” Maruti Techlabs, October 3, 2001. https://marutitech.com/chatbots-work-guide-chatbot-architecture/.

- Kannan, P.V., and Josh Bernoff. “Does Your Company Really Need a Chatbot?” Harvard Business Review (blog). Harvard Business Review, May 21, 2019. https://hbr.org/2019/05/does-your-company-really-need-a-chatbot.

- McDonnell, Marian, and David Baxter. “Chatbots and Gender Stereotyping.” Interacting with Computers 31, no. 2 (2019): 116–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/iwc/iwz007.

- Murtarelli, Grazia, Anne Gregory, and Stefania Romenti. “A Conversation-Based Perspective for Shaping Ethical Human–Machine Interactions: The Particular Challenge of Chatbots.” Journal of Business Research 129 (2021): 927–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.09.018.

- Sanchez, Andrea, and Limary Suarez Pacheco. “Emma: Friendly Presence and Innovative USCIS Resource Available 24/7.” Digital.gov, September 1, 2016. /2016/09/01/emma-friendly-presence-and-innovative-uscis-resource-available-247/.

- Temin, Tom. “Vashon Citizen: USCIS’ New Virtual Assistant Emma Gets Service Award.” Episode. Federal Drive. Federal News Network, 2018.

- USCIS. “Meet Emma, Our Virtual Assistant.” USCIS Tools. USCIS, April 13, 2018. https://www.uscis.gov/tools/meet-emma-our-virtual-assistant.

- USCIS. “USCIS Launches Virtual Assistant - Emma Gives Customers Another Option for Finding Answers.” USCIS Archive, USCIS, 2015. https://www.uscis.gov/archive/uscis-launches-virtual-assistant-emma-gives-customers-another-option-for-finding-answers.

- Verhulst, Stefaan. “Citizenship Office Wants ‘Emma’ to Help You.” The Living Library, May 29, 2017. https://thelivinglib.org/citizenship-office-wants-emma-to-help-you/.

- Villa-Nicholas, Melissa. “Designing the ‘Good Citizen’ through Latina Identity in USCIS’s Virtual Assistant ‘Emma,’” 2019. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1018&context=lsc_facpubs.